Part 0: Da Fundamentenimal Theory Of Music

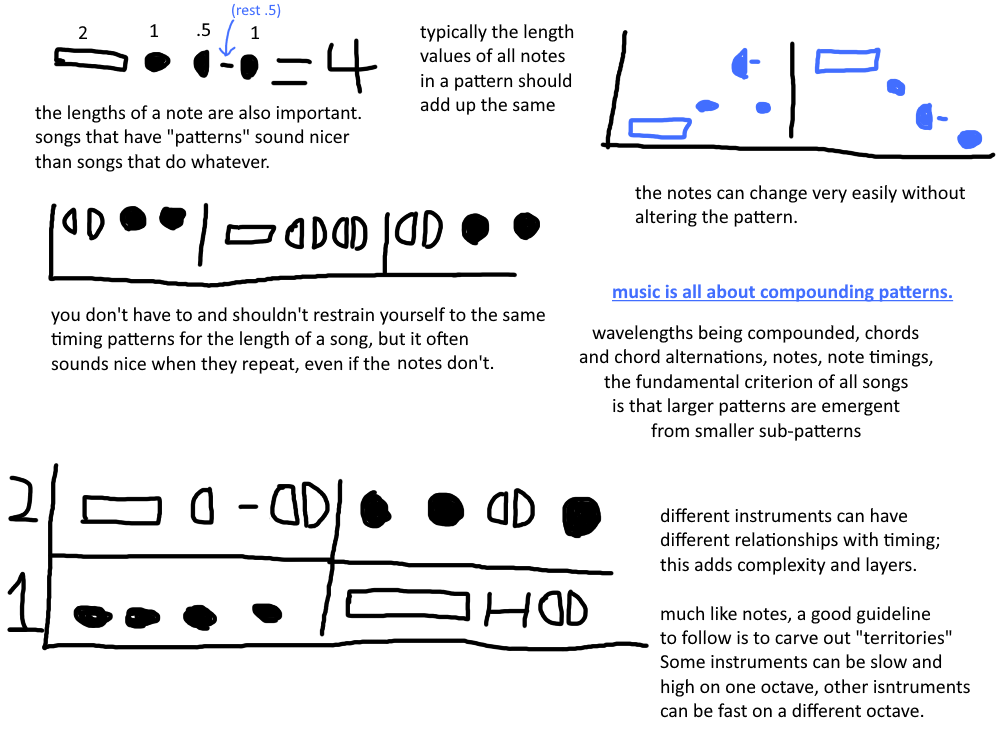

If I had to define what it means to create music in a single sentence, I'd say it is the construction of larger, emergent patterns from simpler ones. Our brains love patterns. This might be a "no shit" kind of sentence, but there's a near infinite way to accomplish the goal of emergent patterns. Each measure is a pattern of the same summitave total of note lenths. Each bar is a pattern of the same summitave total of measure lengths. The beat in a song is a pattern that repeats every bar. The melody is a pattern that comes up several times. The notes of a song, the chords, the way that notes transition, the spacing and timing of the notes, are all repetitive patterns that construct the song. The purest definition of a song is a singular, repeatible pattern composed of hundreds of smaller subunits.

If you're having trouble making good music, going back to the golden rule of constructing patterns is going to be your biggest friend.

Part 0.5: Instrumence

There's a lot that can be said about instruments, but to keep things simple, I'm going to cover the three simplest "roles" an instrument can fill: Melody, Vocals/accompaniment, and chords/base. They're worth thinking about as you go into the next portions of this guide. Finally, you can have instruments that don't fit these roles, and you can have multiple instruments in the same role, but as archetypes of a song, they're important to consider.The melody is the most important portion of a song and it's going to be what people remember. It typically hangs around the C5 octave.

The chords/base are typically much simpler than the melody, but follow the same typical note schema. They're often an octave or two below the melody.

The vocals are the opposite: they're often higher and typically follow the melody, but may break from the timing or go off and do their own thing.

Part 1: Sound

Since it's very hard to make music without using any sound, let's talk about sound.

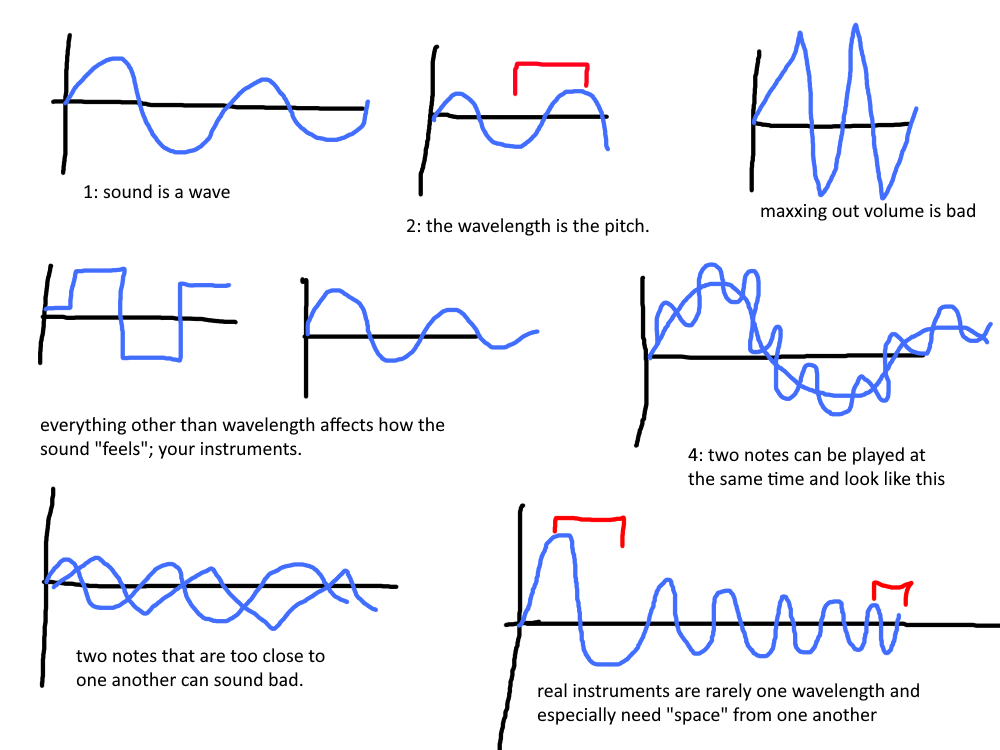

sound is obviously a wave but this is important because there's a lot of things that waves can do. The shape, volume, and patterns of the wavelength affect how we hear the sound, but the only thing that matters for pitch is the frequency. different instruments also often span different wavelengths as you play them; very rarely will they ever be a single pitch.

Two notes being played together compound the wavelength, and this is important, because for every note, there's a set of other notes that sound "good" with it. We hear in octaves, which are "groups" of wavelengths that sound very similar, though mathematically speaking, they scale of sound is logarithmic. C5 and C3 both sound like C, but they're very different; HOWEVER, C5 and E5 at the same time and C3 and E3 at the same time both compound with each other the same.

Part 2: Notes and chords

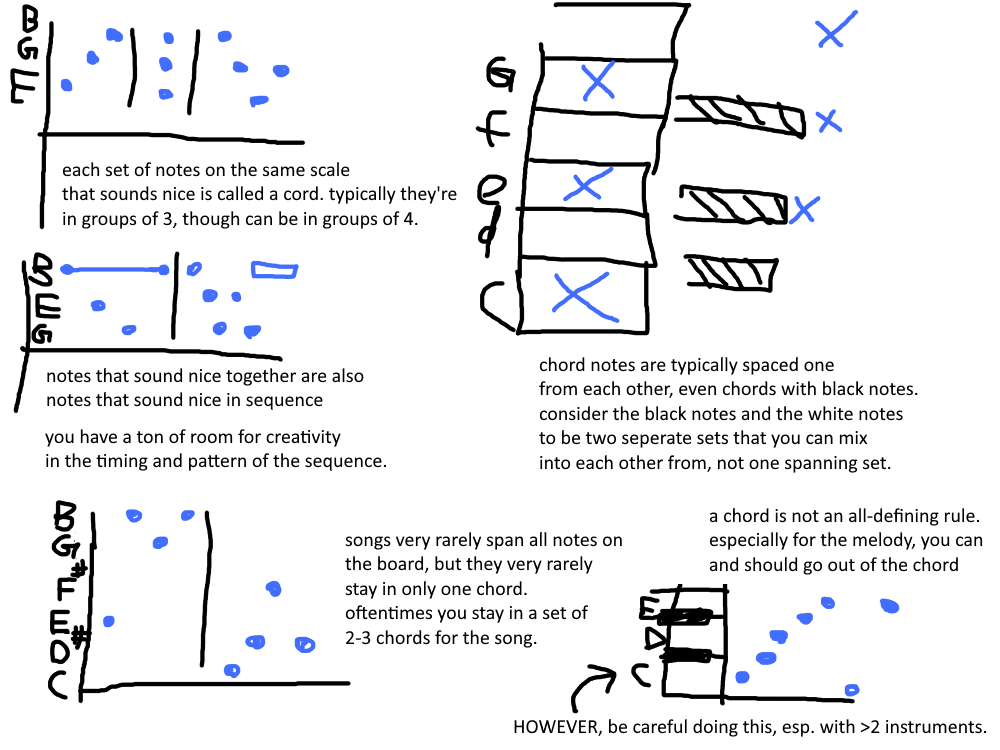

the next is on chords. chords are notes whose wavelengths compound in a nice way. Typically, they're in groups of 3, sometimes they're in groups of 4, and there's a lot to them that I don't know a ton about.

They're important because notes that sound nice when played together also sound nice when played in sequence. (this is also true for chords as a whole, but to a lessser extent). This is the most fundamental thing you should know about music, because from here, you build literally everything. You get to chose the pattern, number of notes in a chord being played at the same time, and spacing between notes in a chord. Even with the same three notes in a 4-measure bar, there's a million different ways to play them.

A chord isn't a rigid restriction on a song. Most songs have 2-3 basic "chords" they change between. Similarly, and especially for the melody, it's almost impossible to only play only the notes in a chord. You can and should go out of a chord, but don't forget what it is when doing so-- think of it as the "home" you return to.

Groups of chords aren't the only defining thing in a song, either.

For every note, there are more notes that sound nice with it in sequence than there are notes that sound nice with it at the same time. The easiest way to find these are to skip one whole note above or below (C->E), move one note above or below (D->C, D->E), or move one black note (D->D#). Additionally, you can skip from one note on a chord to one note just off a chord using the aforementioned three techniques. Lastly, you can skip from one note on a chord to another note on a chord in a different octave, also using the same previously mentioned techniques.

This gives you a lot of options, but when there's multiple notes playing at the same time that constrain things, it's important not to forget what the "safe" rules are. As a rule of thumb, the melody can do basically whatever it wants, but for every other instrument, you have to pay more and more credence to the chords that are active.

Part 3: Timing

Timing is very important, and like notes, timing presents a vast array of choices. It's very easy to shoot yourself in the foot by completely ignoring timing patterns, especially if you're focusing too much on the notes. I don't have a lot to say that's not on the graphic here.

Part 4: Actually making a damn song

This, my friend, is the wild west and also evil dungeon that I cannot guide you through. Partially because I have no idea how to put my process into words but also partially because to give any instruction on this would be talking about genre. Still, I'll give some pointers, since it's very easy to get bogged down at this portion.

Start with the melody but don't be a slave to it. The melody is the "core" of a song, but oftentimes as I add more parts, I'll find it necessary to go back and change or remove parts of the melody for the sake of the song as a whole.

Use grades. Don't throw 50 instruments into things at the same time. Start simple, add on, end simple.

Don't "polish" your song right away. Export it, upload it to your phone, listen to it in different environments. The speakers and conditions you hear things in can vastly change how it sounds. You might notice that an instrument is too loud, or deeply enjoy one segment that doesn't repeat, or realize that things drag on too long.

If it doesn't sound good, it's probably not good. It's easy to get attached to parts that don't sound good in concert or in the context of the whole song. Sounding good is the goal, patterns are how you acheive it. You'll have to change, rewrite, and remove things in order to do this.